I commend Deborah Dunham for her courageous piece on the rising rates of ADD and ADHD diagnosis. Ms, Durham refuses to pull punches, raising a view I have been quite vocal about – the dubious role of teachers in the diagnosis process. Deborah suggests that teachers may be taking the lazy approach instead of the responsible one. She also raises strong arguments about the lack of research about the long-term ramifications of taking Ritalin, the contribution of diet to a child’s mental state and the lack of engagement and stimulation in school.

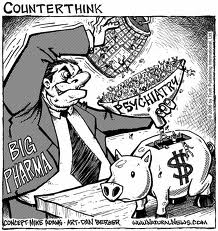

I’m starting to wonder if it’s possible for doctors, teachers and parents to diagnose kids with anything other than Attention Deficit Disorder? According to a new study, the rate that kids are diagnosed continues to increase by 5.5% each year, but are there really that many more kids with ADD and ADHD? It seems like this has become a convenient “out” for many lazy teachers, doctors and parents who don’t know what to do with kids who don’t fit the “mold”.

The rates of ADHD diagnosis in the developed world increased annually by an average of 3% from 1997 to 2006 and 5.5% from 2003 to 2007 in the U.S. But researchers wanted to know–as did we–how accurate these diagnoses really are.

Led by a team of researchers at the University of Basel’s Katrin Bruchmueller, 473 child and adolescent psychotherapists and psychiatrists across Germany were surveyed on how they diagnose people with ADD or ADHD. In three out of the four cases, the described symptoms and circumstances did not fulfill ADHD diagnostic criteria. In fact, many mental health practitioners were found to base their decisions on unclear standards.

For example, male patients were more readily diagnosed when they displayed symptoms such as impulsiveness, motoric restlessness and lack of concentration–all things that can be perfectly normal when growing up. Boys were more likely to be diagnosed than girls, and on the same note, male doctors tended to diagnose ADHD more frequently than their female counterparts.

In short, what the researchers found what that ADHD is over-diagnosed because doctors rely too much on their intuition and not on a defined set of criteria.

All of this is troubling because it means that kids are the ones who are suffering as a result. Instead of taking the time to accurately diagnose them (if there is even anything at all wrong besides just being a “kid”), they are put on brain-altering drugs which is risky for anyone, especially someone who is still young and developing.

More than three million kids in the U.S. take drugs for their supposed difficulty focusing. In 30 years there has been a twentyfold increase in the consumption of these. And while medications like Ritalin may help increase concentration in the short term, not enough is known about the long-term health consequences–although some say drugs like this can stunt a child’s growth, other speculate that they can cause heart problems and even sudden death.

But is it really possible that three million kids in our country really suffer from ADD or ADHD, or has this just become a catch-all diagnosis by lazy doctors, parents and teachers?

We know that an unhealthy diet, sugar, processed foods, stress and a lack of sleep and exercise can all contribute to someone’s mental state. So, it’s entirely possible that our society has become so unhealthy that we are the ones creating these problems in our kids. And it’s not always synthetic drugs that are the answer.

The other issue that could be a major factor here is that kids are not engaged and stimulated in school enough. Taking millions of kids who all have different learning styles and trying to force them to comply and fit into one method of learning does not work. No one can possibly be expected to sit at a tiny, uncomfortable desk for eight hours a day in a classroom with florescent lights and the blinds drawn on the windows. Yet, when a child doesn’t conform, they are thought to have ADD.

Perhaps instead of jumping to conclusions and forcing our kids to swallow mind-altering drugs in order to fit our ideals of how they should behave, all of us–parents, teachers and doctors–should take more time to fully evaluate the unique learning style and personality that each child has and then alter how we interact with them accordingly. That’s not to say that everyone is lazy (because they aren’t) and there aren’t some legitimate cases of ADD (because there certainly are), but research like this points to the fact that we need to take more time and better understand how to consistently diagnose this disorder.