I admit it. The allegations are true. I am a tree-killer!

It’s not my fault, of course. In the short time I have been teaching, the paperwork demands on a teacher have grown from taxing, to barely manageable, to excessive, and now – out of control!

Why? Why, at a time when teachers are being criticised for their students’ low performance data and failure to deliver on outcomes, is the paperwork demands of a teacher so high? Surely time would be better spent developing engaging lessons.

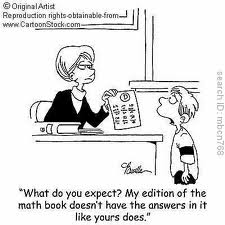

The answer is simple. The rules applying to all teachers are in place to cover the lesser achieving teachers. The assumption is that if a lazy teacher wasn’t told what to do, how to think, what to cover, how to plan and who to cater for, they wouldn’t achieve anything. By forcing teachers to complete crazy amounts of paperwork, they are treating all teachers as if they were inert, fraudulent, apathetic stooges.

Take the planning requirements, for example.

Is planning important? Absolutely! Planning is important for three main reasons:

1. It shows what you are teaching your students in a week, term and year.

2. It helps you organise thoughts and properly sequence the concept or skill you are teaching.

3. It provides a comprehensive guide for a casual relief teacher, should you not be able to teach your class.

As important as planning may be, it can still go overboard. In the summer holidays alone I had to complete first term planners for literacy and numeracy, yearly planners for literacy and numeracy, a 10 page integrated planner for my topic of inquiry (Federation) and weekly planners for both numeracy and literacy. The amount of hours I spend on those darn things doesn’t correlate with how useful they turn out to be.

The rationale that by spending hours upon hours on these planners, an average teacher will become transformed miraculously into a more focussed and effective educator is just plain wrong. On the contrary, it forces some teachers to cut corners by mindlessly copying dull, lifeless units from textbooks. With all that paperwork, teachers often become too concerned with deadlines and time restrictions to go to the trouble of conceiving original and fresh lesson ideas.

And it’s not just planning. There’s professional learning contracts which chart the goals, reflections and progress of the teacher, class newsletters, letter to parents, school policy feedback forms, incident report documentation, worksheets, homework, curriculum night summaries, parent teacher interview folios and I’m sure there’s more, because … there’s always more!

I’m not trying to play the victim here. I love my job and understand the value of the above requirements. It’s just that the sheer amount of paperwork clearly gets in the way of a teacher’s natural desire to spend less time meeting arcane professional standards and more time excelling in delivering fun, vibrant and engaging lessons.

I’d love to write more on this topic, but unfortunately, I’ve got more paperwork to finish.